THE ONLY PROFESSIONAL EVER TO WIN THE LIARS' CLUB CONTEST

THE ONLY PROFESSIONAL EVER TO WIN THE LIARS' CLUB CONTEST

When the Burlington Liars' Club announces its World Champion Liar for 2007, there is one thing that is fairly certain: He or she will not be a politician. Politicians, who are among the world's foremost prevaricators, have their own competitions, including speeches, television a nd radio commercials, so-called debates, elections, and just plain everyday conversations. And so they have been excluded from competing in the Liars' Club's contests since the Club first announced a winner at the end of 1929.

nd radio commercials, so-called debates, elections, and just plain everyday conversations. And so they have been excluded from competing in the Liars' Club's contests since the Club first announced a winner at the end of 1929.

Such an exclusion has not been made, however, for other professional liars -- those who make their livings in the entertainment business. It is not known how many professionals have taken advantage of the opportunity to gain what might be considered the equivalent of an Oscar or an Emmy in the world of Tall Tale Telling, but only one professional has ever been awarded the coveted Liars' Club championship medal -- the Lyre.

That was in the 1935 contest when Jim Jordan of Chicago was proclaimed grand champion. Jordan, now mostly forgotten except as an answer for an occasional quiz show or trivia contest, may be better remembered by those brought up in the days when radio comedy shows were in their prime as one of the title characters of the "Fibber McGee and Molly" show.

STARTED IN VAUDEVILLE

Jordan and his wife, Marian, both natives of Peoria, Illinois, came to radio in 1925 out of vaudeville. In 1927, as Luke in the couple's Luke and Mirandy farm-report program, Jim played a farmer who was given to tall tales and face-saving lies for comic effect. In 1931 the couple, in collaboration with writer Donald Quinn, began a 15-minute daily program over station WMAQ in Chicago called "Smackout" in which Jim, as Luke Grey, played a general store proprietor with a penchant for tall tales and a perpetual lack of whatever his customers wanted: he always seemed "smack out of it." Marian played two characters on the show, a lady named Marian and a little girl named Teeny.

In 1933 WMAQ, an affiliate of the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), picked up "Smackout" for national airing. One of the owners of the S. C. Johnson Company of Racine, Henrietta Johnson Lewis, had recommended to her husband, John, an advertising executive who handled the Johnson's Wax account, that the show be given a chance as a national program for the company. "Smackout" lasted until August 1935.

DEVELOPED “FIBBER McGEE AND MOLLY”

Meanwhile, the Jordans and Quinn developed Fibber McGee and Molly, with Jim playing the foible-prone braggart Fibber -- an amplification of his tall-tale-telling Luke Grey c haracter -- and Marian playing his patient, honey-natured wife Molly. The show, which Johnson's Wax also sponsored, premiered on NBC April 16, 1935, and, though it did not become a full-fledged hit until 1940, when it was rated behind only the Jack Benny and Edgar Bergen shows, it touched a nerve with listeners seeking cheer in the midst of the Depression. One of the network's hottest properties, Fibber McGee and Molly eventually became the top-rated radio show in the country, and held that ranking for 7 of its 20-plus years. The weekly half hour shows (reduced to 15-minute shows in June 1955) ended in March 1956. From June 1957 to September 1959, however, NBC's Monitor included 4-minute vignettes in its programs.

haracter -- and Marian playing his patient, honey-natured wife Molly. The show, which Johnson's Wax also sponsored, premiered on NBC April 16, 1935, and, though it did not become a full-fledged hit until 1940, when it was rated behind only the Jack Benny and Edgar Bergen shows, it touched a nerve with listeners seeking cheer in the midst of the Depression. One of the network's hottest properties, Fibber McGee and Molly eventually became the top-rated radio show in the country, and held that ranking for 7 of its 20-plus years. The weekly half hour shows (reduced to 15-minute shows in June 1955) ended in March 1956. From June 1957 to September 1959, however, NBC's Monitor included 4-minute vignettes in its programs.

The episodes, a new one each week except for the normal summer breaks, generally took place at the McGee house at 79 Wistful Vista where Fibber, who didn't seem to have a job, would start some mundane task (like filling out a catalog order form or tuning a piano) or some hare-brained scheme (like digging an oil well in the back yard) until interrupted by the "bong-bong" of the door chimes. Fibber would then get into conversations, arguments, or verbal "joustings" with the neighbors and friends who had stopped by. Molly generally indulged his foibles, but would respond to his bad jokes with "T'aint funny, McGee," which became a national catch phrase. And she would gently soften his return to reality as his schemes inevitably failed.

THE CLOSET

Among the show's familiar routines was having one of the McGees, usually Fibber, open the door of their overstuffed closet -- despite the other's "Don't open that door" -- and being buried by a clattering avalanche of the contents. What tumbled out was never clear, except to the sound-effects man, but the end of the avalanche was always signaled by the sound of a clear, tiny household hand bell, and the declaration "I gotta get that closet cleaned out one of these days."

"The Closet," which began as a one-time stunt -- with Molly as the victim, was developed carefully and was not overused, rarely appearing in more than two consecutive shows. And the closet was rarely opened at exactly the same time from show to show. It became the best-known running sound gag in American radio's classic period, leaving Jack Benny's basement vault alarm running a distant second.

"The Closet" was even used in one episode to catch a burglar who had tied up McGee. McGee informed him that the family's silver was "right through that door, bud . . . just yank it open, bud." Taking the bait, the burglar was buried in the avalanche long enough for the police to handcuff him. On one or two episodes, Fibber opened the closet door, only to be met with complete silence. As audience members chuckled slightly or held their breath in anticipation, Molly explained that she had cleaned the closet the day before. The gag was not over, however, as the closet soon became cluttered again.

THE CAST

The steady stream of neighbors and friends who stopped by the McGees’ house, each a character in his or her own way, added to the confusion and hilarity of the situation at hand. Marian supplied the voices for three of the visitors: Grandma; Teeny, the girl next door; and Mrs. Wearybottom. Teeny, also known as "Little Girl" and "Sis," was a precocious youngster who usually tried to cadge loose change from Fibber, and ended half her sentences with "I'm hungry!" and, especially, "I betcha!" Teeny was also known to lose track of her own conversations, switching from telling about to asking about whatever it was. Then, when Fibber would repeat what she had been telling him, Teeny would reply "I know it!" in a condescending way.

Besides Fibber, another blowhard, who made regular visits in the show's early years before breaking away to do his own show, was the McGee's neighbor Throckmorton P. Gildersleeve (Harold Peary). He had a booming voice, and Peary used the power of his voice for maximum effect. When Gildy shouted "Oh McGEEeeeeeeeeeeee" one could almost hear the windows rattle. McGee and Gildersleeve seemed often to be one step away from throwing punches at each other.

Announcer Harlow Wilcox visited also and wasted no time in linking the sponsor's products -- Johnson's Self-polishing Glo-Coat for most of the show's run -- to the topic at hand. In this way the show had no commercial breaks because the plugs by Wilcox, whom Fibber called "Harpo" or "Waxy," were usually quite funny and part of the show. As Wilcox gave his pitch you could sometimes hear Fibber and Molly groaning in the background, fully regretting that they had said whatever it was that triggered something in Wilcox, setting him loose with his spiel.

Snooty Mrs. Abigail Uppington (Isabel Randolph) dropped by, even though the McGees were clearly below her social standing. "Uppy" was quite a friendly person, but it was obvious that she looked down her nose at Fibber and Molly. In response, Fibber delighted in deflating her pretensions.

At the other end of the social scale was Horatio K. Boomer (Bill Thompson) a petty thief and low-life who sounded like W.C. Fields. Thompson also played the parts of Nick Depopoulous, proprietor of a Greek restaurant with a tendency toward verbal malapropisms; the "deef" Old-Timer ("That's pretty good Johnny, but that ain't the way I heared it"); and Wallace Wimple, the henpecked and sometimes physically battered husband of his "big old wife Sweetieface."

Among the semi-regular visitors were Mayor LaTrivia (Gale Gordon), an easily-flustered man with a quick temper whom Fibber delighted in getting into arguments with; and Doc Gamble (Arthur Q. Bryan, who also voiced Elmer Fudd in the Looney Tunes cartoons), who made housecalls often to his regret because he, too, was subjected to name-calling, insults, and arguments. The insults that he exchanged with McGee were quite harmless with no animosity intended.

The most unusual character might have been the McGee's black maid, Beulah, who was voiced by a Caucasian male, Marlin Hurt. Beulah's usual opening line, "Somebody bawl fo' Beulah?," often provoked laughter among the live studio audience, many of whom, seeing the show for the first time, did not know that the actor voicing Beulah was neither black nor female.

Minor characters included Alice Darling (Shirley Mitchell), a ditzy aircraft-plant worker who boarded with the McGees during the war; and Molly's Uncle Dennis (Ransom Sherman), an alcoholic living with the McGees, who was seldom seen but sometimes heard making noise.

Some characters were names only, never being heard. Foremost in this group was Myrtle, or "Myrt," a telephone operator whom Fibber was friends with. A typical Myrt sketch started with Fibber picking up the phone and demanding, "Operator, give me number 3-2-Oooh, is that you, Myrt? How's every little thing Myrt?" This was typically followed with Fibber relaying what Myrt was telling him to Molly, usually news about Myrt's family, and always ending with a bad pun.

The show also used two musical numbers per episode to break the comedy routines into sections. For most of the show's run, there would be one vocal number by The King's Men (a vocal quartet consisting of Ken Darby, Rad Robinson, Jon Dodson, and Bud Linn), and an instrumental by The Billy Mills Orchestra. For a short time in the early '40s, Martha Tilton sang what was formerly the instrumental. And from time to time, well-known guest stars, such as Zasu Pitts and Perry Como, would play parts or sing a musical number.

1935 LIARS' CONTEST RESULTS ANNOUNCED OVER NATIONWIDE RADIO NETWORK

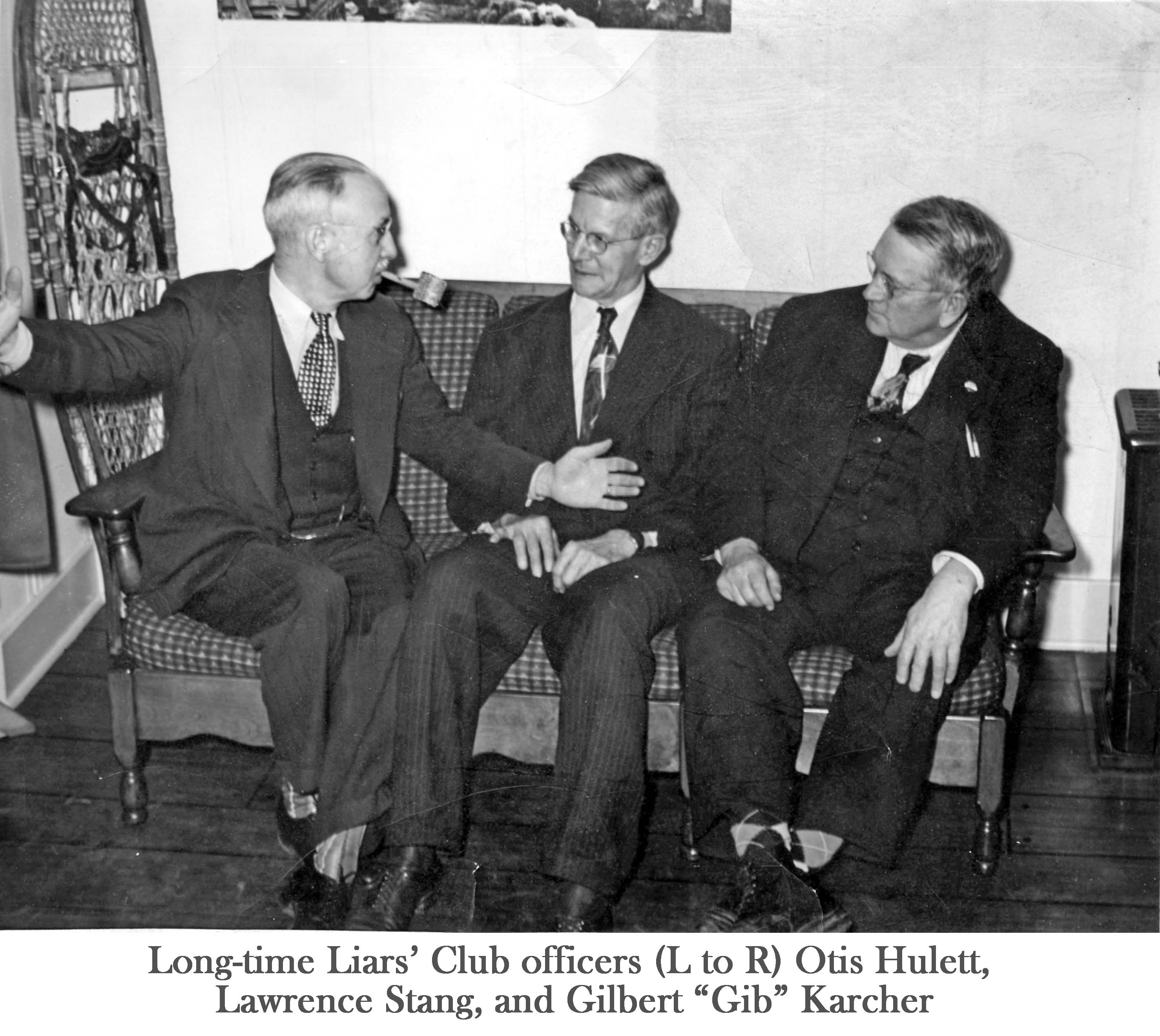

New Year's day 1936 marked the third year that the Burlington Liars' Club announced its champion liar over a nationwide hook-up on the NBC network. Interest in the Club had spread fr om its beginning as a practical joke at the end of 1929, when Burlington residents, generally past retirement age, were the only contestants, to its becoming a national and international contest. Close to 5,000 entries were received during 1935, coming from every one of the then 48 States, every Canadian province, Newfoundland, Alaska, Mexico, England, Denmark, the Hawaiian Islands, Cuba, Africa, Costa Rica, Australia, and Switzerland. The Club's officers -- Otis Hulett, Lawrence Stang, and Gilbert "Gib" Karcher -- were invited to studios in the Merchandise Mart in Chicago for the 15-minute New Year's day program, where Hulett gave a brief sketch of the Club, a number of 1935's outstanding lies were read, and the champion liar was announced.

om its beginning as a practical joke at the end of 1929, when Burlington residents, generally past retirement age, were the only contestants, to its becoming a national and international contest. Close to 5,000 entries were received during 1935, coming from every one of the then 48 States, every Canadian province, Newfoundland, Alaska, Mexico, England, Denmark, the Hawaiian Islands, Cuba, Africa, Costa Rica, Australia, and Switzerland. The Club's officers -- Otis Hulett, Lawrence Stang, and Gilbert "Gib" Karcher -- were invited to studios in the Merchandise Mart in Chicago for the 15-minute New Year's day program, where Hulett gave a brief sketch of the Club, a number of 1935's outstanding lies were read, and the champion liar was announced.

And what was the tale that Jim "Fibber McGee" Jordan submitted that won him the 1935 title of grand champion liar and the Club's "diamond studded" medal? It was about a rat and was told as follows:

"Two years ago the winter here was so cold that it drove a large rat into our house for shelter. Do whatever I would, I could not catch him, even with the most cleverly baited traps. Finally I hit upon an idea. "The cold drove you in here," says I to myself. "And the cold will catch you." That night I brought in our largest thermometer and hung it in the kitchen, putting a large piece of cheese directly beneath it. Next morning I had Mr. Rat -- for the mercury had dropped so low during the night that it had pinned both him and the cheese to the floor."

The story of Fibber McGee's win was carried by over 90 percent of the daily newspapers across the nation, as well as by other newspapers, including Burlington’s two weeklies -- the Standard Democrat and the Free Press. A week later, the Standard, while acknowledging the advertising value of having Burlington make headlines throughout the country because of the Liars’ Club, also said that the awarding of the championship to a "professional" raised the question as to when a liar ceased to be an amateur. In sports, it said, it was when a man took money for his ability, but such a division point would hardly be fair in lying as most honest lies were told for personal profit. Heretofore, it added, only politicians had been classed as professionals, but it suggested that the Club consider drawing a finer line.

While it is not certain that the Liars' Club ever officially took the Standard's suggestion to extend the ban to all professionals, no professional liar has won the annual contest since Jordan / McGee's win in 1935. Whether any may have “snuck” their handiwork past the judges is not known, although in 1974, Otis Hulett said he could not recall any “famous person” other than Jordan ever entering the contest. The Club, however, has not completely ignored the efforts of professional liars. In the early months of World War II, the Club gave special recognition to Paul Joseph Goebbels, Nazi propaganda minister, who was awarded the "Medal of the Order of the Double Cross." The interest in the Liars’ Club was so widespread at that time that Fox Movietone and Paramount newsreel cameramen were on hand at Club secretary L. J. Stang's store in the Chestnut Street loop to record the ceremonies.

Information on the history of the Fibber McGee and Molly show was obtained from several internet sources, including en.wikipedia.org, nytimes.com, radiohof.org, time.com, archive.org, otrsite.com, and compusmart.ab.ca.